Art

Art as Self-defense: the work of Rajko Radovanović

On a sunny day last spring, I met artist Rajko Radovanović for coffee on Trg bana Jelačića, the main square in Croatia’s capital, Zagreb. I ordered coffee with cream, Radovanović Earl Grey. The artist’s tea arrived an assemblage of white china: a saucer and teacup topped by a smaller saucer, tea bag, sugar, a lemon wedge, and a tiny pitcher of milk.

“Skulptura!” he chuckled, as he began to dissemble the tottering tower to make his tea. Sculpture. It was a seemingly trivial utterance, simply an amused observation, but it actually reveals much about Radovanović and his artistic practice. Motivated by a need to deconstruct and create (or recreate), Radovanović sees artistic potential in everything, and while his approach is measured and analytical, it is often tinged with clever humor.

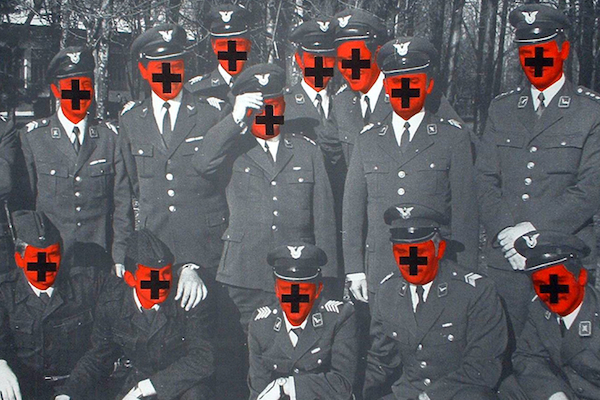

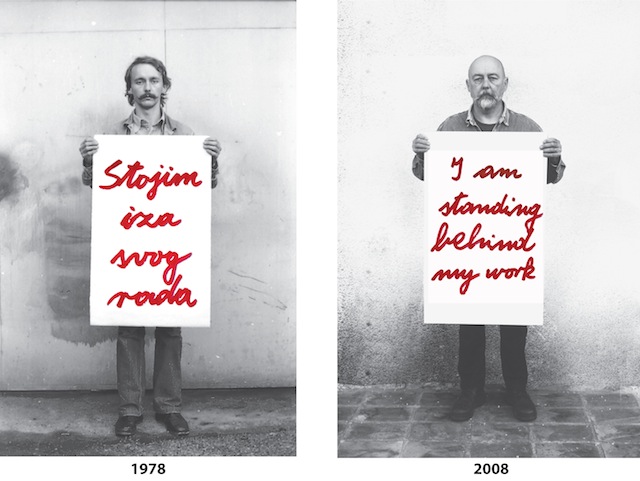

That’s not to say that his work is all fun and games. His creative practice has, for decades, been driven by weighty themes such as repression, social injustice, and identity. Radovanović’s artistic beginnings go back to 1970s Zagreb, then part of Yugoslavia. Together with a small collective of artists, he joined Podrum, one of the first independent artist-run galleries in the region. Their activities, termed New Artistic Practice, were focused on new and experimental approaches to art and reaching a wider audience through public participation.

“This square is a place where we used to do loads of artwork,” he said, gesturing toward Trg bana Jelačića. “Taking art to the people. That was the basic idea. Art shouldn’t be closed in an institution. I know the museum exists to collect art. That’s fair enough . . . But not everybody goes there.”

“I had this idea to exhibit art in the restroom . . . I thought to put art in the most private, accessible place in the home, so you have something to look at while there,” he says of an early attempt to offer an alternative to museum-style art viewing. For the first installment of the project, Radovanović used the restroom in his parents’ flat, but his father was not too thrilled with the idea, so he recreated it in Belgrade at an art exhibition.

Other works from this period dealt more directly with personal identity within the context of a repressive regime, for example a small piece created for the shop window of artist Željko Jerman’s photo lab, where one artist would display something every month.

“I had just come from the army, so I used three photographs of [my hair] being shaven, and I [reinterpreted] these three photos as police profile photos. I also used the document from when they sent me to military jail due to non-discipline. What happened was, some very conscious citizen [saw it in the window] and reported it to the local police, they reported it to the military police, and the military police came to my parents’ flat to talk to my father, who was an army officer . . . So my father was ordered to report to the general, and they decided that I’m a young guy who went to the army and now I’m a little disappointed with my life. [They thought], he’s young, he’ll grow out of it. He never did!”

Indeed, not only has Radovanović continued to create art since then, he also considers his artistic practice integral to his personal identity. After relocating to the UK to study art at Brighton University and then eventually emigrating to New Orleans, Radovanović finds little value in defining himself in terms of nationality. After all, he points out, the country of his birth – Yugoslavia – doesn’t even exist anymore.

“That’s another reason I’m making art. It’s what defines me,” he explains. “. . . The artistic act is the only valid form of self-identification and a clear modus of existence for an individuated human being. Selfishly, this is the only way to keep my head sane. I am the only one in charge of deconstruction and the following construction. Nobody can interfere with this. It is out of reach from any legal, political or, God forbid, military intervention.”

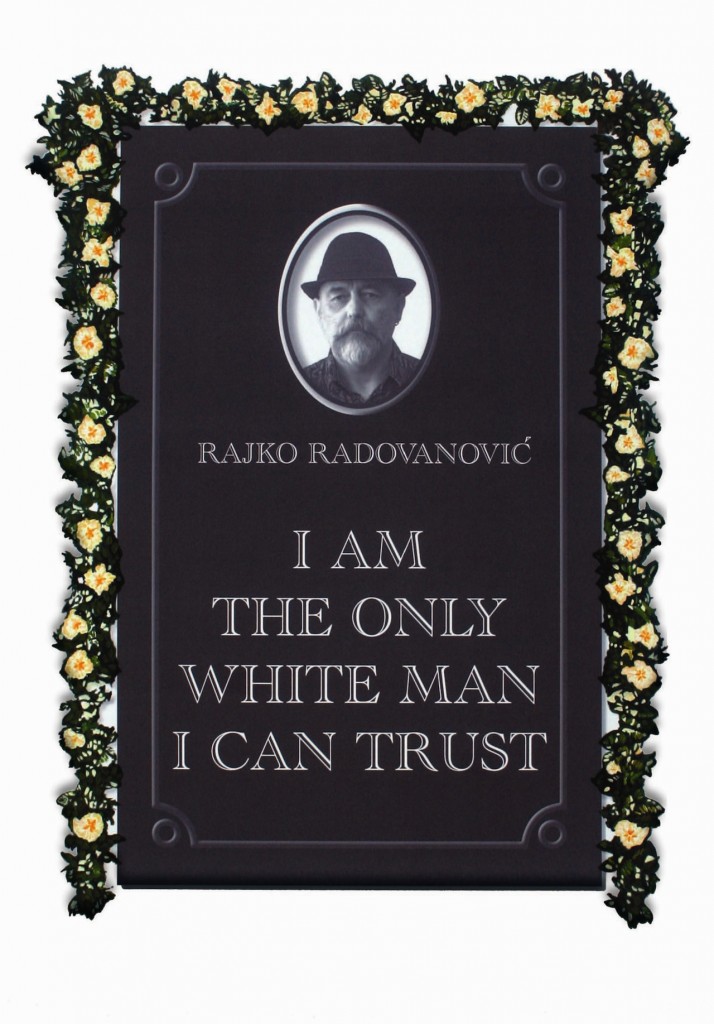

Since relocating to New Orleans in 2008, Radovanović’s work has continued to investigate the subject of identity, often in terms of a new identity recently ascribed to him. For the series ‘Futility’ of Identity, comprised of photographs of the artist accompanied by slogans such as “I am the only white man I can trust” and “Some of my best friends are white,” Radovanović explains that until recently, he was predominantly defined by his foreignness. In New Orleans, however, he has experienced a completely new form of visual identification: to his black neighbors, he is a white man. These works drive home the idea that identity is always relative, and no matter how hard we try to assert our own individuality, we will always be defined by our affiliation with groups – family, village, tribe, nation, gay, straight, white, black – to which we are supposed to belong.

They also comment on the concept of political correctness, which Radovanović believes simply creates an illusion that all is well, and in the process, sidesteps important issues. But art can help by creating opportunities for interaction between groups and by more openly addressing such taboos. Essentially, he says, art observes the same issues as media or politics, but from different angle.

Radovanović stresses that his aim is not to offend, but to deconstruct existent situations or ideas and reconstruct them in a provocative way. “I grew up believing that a work of art should contain ethical, social, political and aesthetic components . . . . The basic concept of my art is simple: deconstruction of the existing reality presented to us by the relevant ‘authorities’ – parents, teachers, priests, politicians, etc. – in conjunction with the modern media. Deconstruction creates construction, which is usually positive in the world of art.”

For Radovanović, it’s important that his work is not just an illustration of reality. He strives to deconstruct reality and from it, create something new. It’s an activity he believes is integral to making work that carries a message and is socially conscious, and it’s something he does constantly. “Just walking through space, I’m deconstructing,” he says.

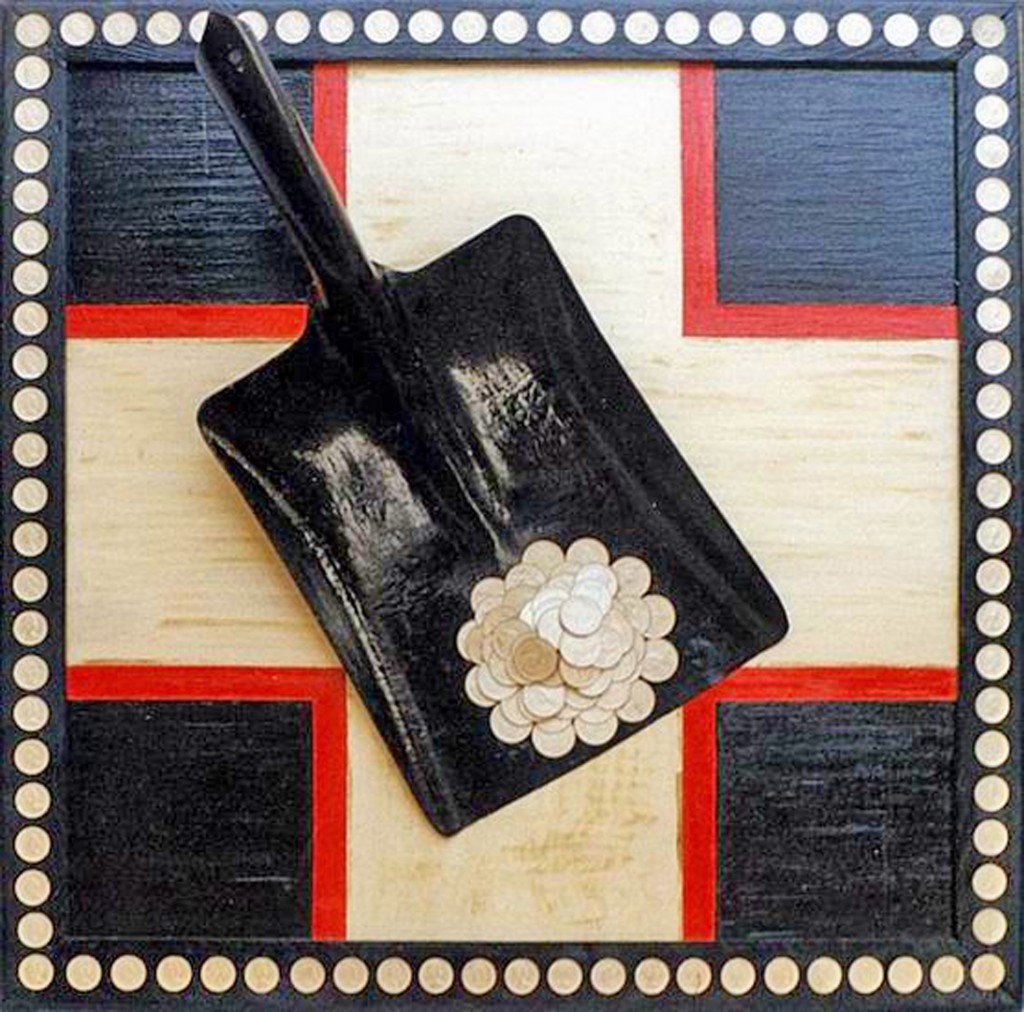

Even just noticing something visually provocative that relates to a relevant social or political issue is often enough to result in an entirely new body of work, for example the batons that have become a motif in Radovanović’s current series, Angry American Artist (A Study Towards Greater Anger).

The idea for these images, in which Radovanović uses batons and handguns to create crosses draped with funeral flowers, actually combines several sources, from Occupy Wall Street to the imprisonment of Russian punk rock band Pussy Riot, as well as the questions What would an angry American artist use? and What should an angry American artist use? Not physically, of course, but to visually symbolize discontent and encourage awareness and critical thought.

“To do socially conscious art, you have to feel some kind of anger,” says Radovanović. “We all know that life can be better. We don’t live in a perfect society . . . The most important thing: we can’t change the world by jumping on barricades. But what we can do is not allow others to censor us and not allow ourselves to be censored.”

Written by: Elaine Ritchel