Art

Art collective Fokus Grupa investigates contemporary artistic practice

Last year, artists Iva Kovač and Elvis Krstulović, who have been collaborating since 2005, officially joined forces as the artist collective Fokus Grupa. As the name suggests, their work incorporates extensive research, collaboration, and dialogue. Bringing together various media, including film, installation, and works on paper, as well as discussions, workshops, and lectures, Fokus Grupa examines the relations – personal, societal, historical, financial, legislative – that surround artistic practice.

Fokus Grupa has participated in a number of exhibitions and conferences, and also co-edits and co-publishes Politics of Feelings / Economies of Love and co-curates Gallery SIZ. This month, Fokus Grupa is participating in the exhibition Dear Art at Calvert 22 Gallery in London and at 25fps, an experimental film festival in Zagreb.

Recently, Fokus Grupa took some time out to tell us more about their artistic practice and current work.

Can you tell us a bit about Fokus Grupa as a collective? How did you start working together?

There are at least two answers to this question. The decision came out of our artistic and political understanding of art practice as a collective endeavor — an opposition to the paradigm of the creative individual that still dominates the art world and art market especially. A more biographical answer would be that we started our practice while already living, learning, discussing and debating our individual practices and art in general, so it was only logical to start also working together. … Fokus Grupa regularly also includes other people in our projects, although the two of us are the core. We are also active in collectives SIZ and k.r.u.z.o.k.

What are some of the major themes in your work?

Our practice, as much as the formation of Fokus Grupa itself, is influenced and continues the tradition of conceptual and critical art practices, and more precisely — institutional critique. Our particular field of interest is quite wide, but it could be said that we are interested in various cultural forms of production of meaning, whether these forms belong to art, politics, media, law, etc.

We are exploring the ways in which legal, ideological, and spatial structures that make the environment of art also influence this art, and determine our understanding of it. This means that sometimes we are more interested in the economical and legal background of some cultural manifestations than in their apparent presentational format, or if the form itself interests us, it is often because it reflects certain economical, ideological and/or legal interests. The format of our work is on the edge between representation and iconoclasm, image and language.

On of your ongoing activities is researching the “politics of art.” What is the relationship between politics and art? Is art always political?

We work under the assumption that society, and by extension art practice, is permeated with politics. What this means is that aspects of our daily lives as well as our work are a result of and have political consequences. This is true also when it’s not apparent, for example the way homes are constructed is based on the way a certain society understands or promotes private life. Many of the decisions made by the architect do not have to be conscious political decisions to be a result of a particular worldview, or if you want — ideology. This implies that art is always political, whether the artist wants this or not, and its politics are often in contrast to what it propagates.

Your artistic practice includes workshops focused on issues that face contemporary artists. Do you view projects like these as artistic works?

We are more inclined to use the term “artistic practice” as opposed to art works, since the term belongs to a more relational understanding of art and culture production. Recently Otolith Group from UK used the term “integrated practice” which represents a heterogeneous practice that includes discursive, educational, social events, as well as exhibitions, publication and distribution and is historically linked to non-commercial feminist film practice from the ‘80s. We really liked this term as we feel it better describes how we see our work.

What was the outcome of these workshops?

The intention of the workshops was to promote a critical attitude toward labor conditions of artists in the current moment, to make artists aware of their rights, as well as to imagine a fairer system. The immediate result of the workshop was a small publication containing the certificates or pseudo contracts drafted by the artists who attended the workshop. These certificates were attempts of the artists to use this legal form to express what they believe in, in terms of their right to be in control of the way their work and they themselves should be represented, reproduced, or credited. We also published a text in a magazine by ArtLeaks that was influenced by our experience with the workshop.

Are there any artists in particular who are particularly influential or inspirational to you?

This changes with time, but artists like Sanja Iveković, Mladen Stilinović, Goran Đorđević, Hans Haacke, and Martha Rosler remain our point of reference. From the somewhat younger generation, Sharon Hayes, Sarah Morris, Hito Steyerl, Maria Einchorn, David Maljković, Claire Fontaine, Chto Delat, and Slavs and Tatars are a great inspiration. Historical examples [include] the Berlin Dadaists Georg Grosz and John Heartfield and the Russian avant-garde, and from our own generation, REP Collective, Aleksandra Domanović, Rafaela Dražić, and Ištvan Išt Huzjan.

But there are many more, and in a way you always do injustice to many by pointing out a few. We are also often influenced by books and movies, design and architecture.

You are participating in the upcoming exhibition Dear Art at Calvert 22 Gallery in London. Can you tell us something about the work that will be on view?

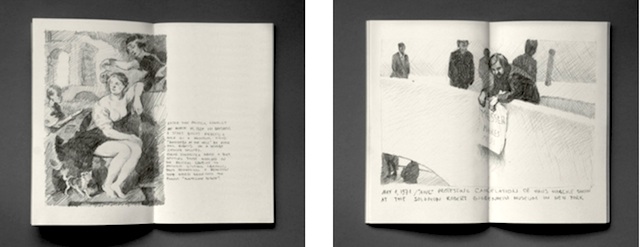

At Dear Art we are exhibiting an open sequence of drawings under the title Pjevam da mi prođe vrijeme (I Sing to Pass the Time) — a title we appropriated from a singer-songwriter from Croatia, Arsen Dedić. In the song he expresses a disbelief in political songs and what they can achieve. We wanted to use this title to confront it with what the work displays, somehow to not forget that any political action within the art sphere is soon appropriated.

The drawings were done from different source materials we have gathered in our research, and they index political and/or legal actions by art workers throughout the 20th century in order to change the position of the artist in society, change the art system, or the way art is understood. These actions were not done as “artworks,” but as political actions.

In general, what we wanted to achieve was to provide alternative narratives to the dominant art historical narrative that provides an understanding of art practice as an isolated aesthetic discipline. We also tried to show how art need not display political slogans to be political: that art production is a part of broader political changes makes art political — not its iconography. Another important aspect of the work is that we wanted to make a tribute to ephemeral, often forgotten events that we believe are important.

What projects are you currently working on?

Maybe the two most important events that we are preparing for the next year are Between Democracies: 1989-2014, an international conference and a group show in Johannesburg, to which we were invited by the art historian Ljiljana Kolešnik, and a solo show in SKUC Gallery in Ljubljana. One work is still in development, so we can only say that we will be doing a reenactment of a “performance” by Jean Jacques Rousseau.

Another project we are developing involves a lot of bureaucracy around getting the permit to make a copy of the head of the horse of Josip Ban Jelačić — an equestrian sculpture central to the Croatian national narrative, which makes it very complicated to reproduce.

How do you see your work evolving in the future?

The trick to surviving life as an artist is not to think to far ahead, so we won’t. We recently moved to Rijeka. … During this fall we plan to get a bit bigger space, so we believe this will reflect on our production in terms of the size of works and materials we use.

Interview by: Elaine Ritchel (@elaineritchel)

Images courtesy of FokusGrupa