Art

Artist Marko Tadić on making Borne by the Birds

From delicate drawings and collages assembled from old postcards and scraps of paper to small wooden sculptures resembling pared-down theater and film sets, the work of multi-media artist Marko Tadić illustrates his meditations on fictitious narratives, imagined journeys, and perceptions of time and place. Tadić is also well versed in the art of animation, using stop motion to create lyrical visual journeys hinging on displacement and ambiguity. To date, Tadić has completed three short animations – I Speak True Things (2009), which won the Radoslav Putar Award in 2008 and was subsequently acquired by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb, and We Used to Call it Moon (2011), now part of the Filip Trade Collection housed at Lauba.

Tadić completed his third animation, Borne by the Birds, earlier this year and spoke with us about his creative process and the importance of location to his work.

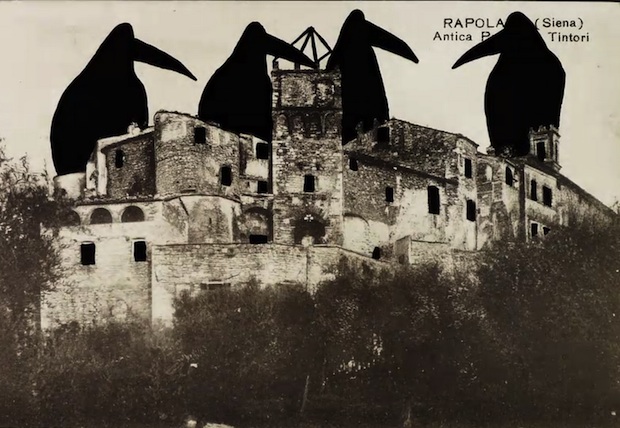

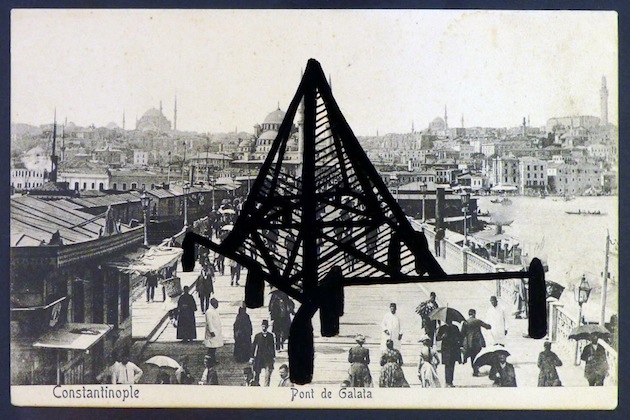

Borne by the Birds opens with a short segment featuring two actors who set the stage for the ensuing animation – the visual journey of a man who lived three hundred years. Using India ink to draw on transparent foil placed over vintage postcards, Tadić transforms static images into sets for his wandering protagonist. His mark making seems at once organic and strategic in the way it complements or, at times, implements the formal elements of the postcards themselves.

“The drawing is the best part,” says Tadić, who worked from 8 to 12 hours a day on these drawings while in residency at HIAP on the island of Suomelinna, Finland. “I have a general idea of what I would like to do [with the postcard]. First I look at it a while and see what comes up. When I start [drawing], it just kind of flows.” The drawings for Borne by the Birds took three months to complete, and postproduction lasted nine months. “Each postcard was like one short film. Each line, one photo. So this animation has around 9 or 10,000 photos,” says Tadić, explaining that he sets up his camera on a tripod, positioning it over a fixed frame on a table where he places the postcards to photograph them.

After completing the drawings, Tadić pieced them all together to create a “rhythm” that tells the story he had in mind.“Half of the time was the choosing process. I spent a lot of time in this shop with old postcards [in Helsinki]. I would go there daily, and I’d buy about 10 postcards, and it would take me about two hours to choose,” he says. Tadić notes that he chose not to cover up the descriptions on the postcards because many of the locations were significant to him in some way. “I left them as references, because it was important to me when I was choosing them. Some of the landscapes are there because they suit my style, but mainly all of the postcards are chosen.”

Location has a curious place in Tadić’s work. While the notion of place is a significant theme, locations themselves are only ever referenced. In other words, they don’t drive narrative or relate to a specific event or overall message. Though it doesn’t directly reference Suomelinna Island, for instance, Borne by the Birds is in fact very much tied to the small community, where Tadić was living at the time. “I think the island itself gave a lot of inspiration [to the film],” he says, speaking about the atmosphere of the Finnish island – cold, windy, and starkly beautiful – and how it contributed to the film’s melancholy mood.

“I really loved it there,” he reflects. “On the island is a dry dock. I wanted to do the beginning [of the film] with actors at that special place, where they repair wooden ships. When I first saw the dry dock, I was stunned, because it was filled with ships. By the time we shot the scenes, there were only two of them.”

Tadić adds that the story itself references literature he was reading at the time. “I was inspired by this short article I read about a Chinese man who lived for four centuries. It’s not true, of course, but it was written so nicely. . . . He was a ninja, a general in the army, an herbalist, and a healer, so during these 400 years, he did everything. . . . In the beginning, [I thought] I could do a short summary, a cut of recent history. In the end it turned into this poetical journey of an abstract figure who wants to be immortal, but when he gets immortality, he wants to lose it again.”

“In all my works,” he continues, “I try to avoid direct references to political situations in the world. I try to speak in a more general, subtle way. . . . Should we hate the world? Should people die, or not? What is immortality? It kind of touches these points that everybody thinks about.”

View the complete animation here. View other animations by Tadić on Vimeo.

Written by Elaine Ritchel (@elaineritchel)

Images courtesy of the artist.