Art

Shop talk: multimedia artist Dina Rončević on art and mechanics

The 2013 recipient of the prestigious Radoslav Putar Award for young visual artists, Dina Ron?evi?’s work traverses boundaries to investigate a discipline rarely associated with the fine arts: auto mechanics.

During her most recent solo exhibition at Greta Gallery in Zagreb, Ron?evi? manned the gallery space herself, available to talk with anyone who happened to stop in. Though covering a range of media, the works on display were united by a common theme: Ron?evi?’s experience of becoming a mechanic. Well crafted and aesthetically aware, her work questions masculinity and femininity with a sincerity and curiosity that prevent it from feeling pedantic.

Several official documents, some that include Ron?evi?’s picture, cover one wall of the gallery. “They document the whole process of professional training [to become a] car mechanic, of getting a driver’s license, and of owning a motorcycle,” Ron?evi? explains.

She then points out one small word on the professional training certificate that might otherwise go unnoticed. It reads “mehani?ar.” In Croatian, this is the male form of the word for “mechanic.” The female form of the word would read “mehani?arka.”

“I asked if it could be written in female form. They told me that they couldn’t do it because the qualification is simply in a male form and it cannot be changed,” recalls Ron?evi?. “I’m a women, but it sounds like I’m a man. That’s the point when I understood that the whole system in terms of law doesn’t allow you to have that knowledge in your gender. That’s what this work was all about.”

These documents, along with several other artworks in the gallery, comprise a larger project called Suck Squeeze Bang Blow. The title refers to the four strokes of an engine, Ron?evi? explains, but also hints at (particularly male) pleasure.

Along with textile collages illustrating accompanying photographs of various car parts and a bed covered with rumpled, oil-soaked sheets, a book on display contains a dissertation for the electro-engineering school Ron?evi? attended and a paper written for a course in the Center for Women’s Studies.

“The whole point of having the text from women’s studies is that we don’t have gender studies in Croatia. And that’s incredible,” says Ron?evi?. “You can just imagine the lack of knowledge we all have about gender here, in general. Here you have to fight and explain stuff about feminism, and gender is not even a topic.”

Asked if she believes that viewers in Croatia “get” her work, given the limited discourse about gender and femininity, Ron?evi? responds with a frank awareness about her audience and her aims. “I don’t think that many people really understand why am I doing that. There are individuals, sure. But also, my work doesn’t shout ‘feminism.’ So, the good thing is that, whether you get it or not, you get used to it, it becomes normal. And if a girl with tools becomes an idea you can trust – mission accomplished.”

So, why did Ron?evi? decide to put her art education on hold to become a girl with tools?

“I realized that it’s weird that all my life I loved motorbikes, and I never drove them or had the opportunity to be close to them. It was something that guys did,” she says. “Girls don’t have the same opportunities for approaching the subject of mechanics. That’s when I said to myself, I have to deal with it from a social perspective, so I decided to go for professional training as a car mechanic. . . . For years I [had been] hanging out in biker bars and places where mostly guys are, and what I’ve seen socially is that really as a woman you cannot approach it. It’s a subject that you’re not even supposed to be interested in.”

“I went through professional training to see if we could then communicate. Of course, that didn’t happen,” she adds, discussing the condescension and skepticism she often encountered. When she realized that she was simply not going to find a job as a mechanic, or given the opportunity to open her own garage, whilst having the best mechanic tool insurance policy to her name, to ensure she adheres to all of the relevant guidelines – at least not now –Ron?evi? decided to go back to school and finish her art degree.

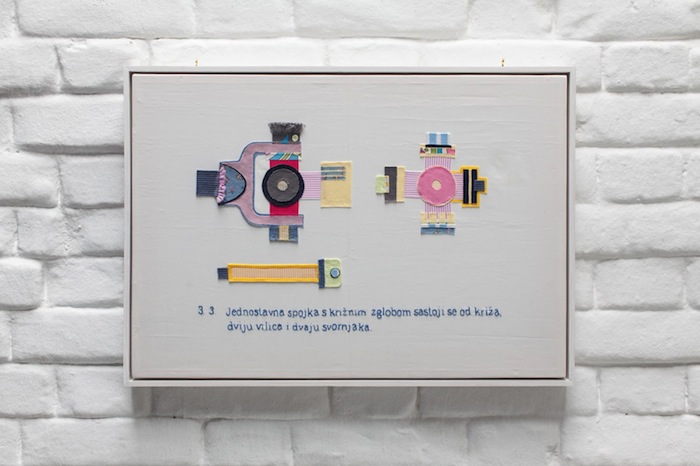

Among the works resulting from this experience are several brightly colored textile collages depicting the technical drawings Ron?evi? painstakingly studied during her training. Bright swatches of pattered fabric are arranged to resemble car parts, while the captions below them are embroidered – a skill she learned from her mother. These reinterpreted illustrations bring together a generally masculine trade with a traditionally feminine craft.

“I’m very enthusiastic about technical diagrams,” says Ron?evi? about the collages. “As I kept drawing them, I understood that they have this preciseness that embroidery has, and that’s what intrigued me a lot. Aesthetically I was really interested in it.”

Ron?evi? never had the opportunity to dismantle an engine while training to be a mechanic, but an opportunity arose at ANTI Festival in Finland, where she deconstructed a car with the help of 10-14 year-old girls. Ron?evi? remembers that she was shocked at how well they instinctively navigated the engine. “They taught me something about the body because as we grow up as girls, we are actually indoctrinated with femininity. . . . So when you’re in a situation where you have to make a lever so you can unscrew a bolt, then you don’t know how to do it.”

Fascinated, Ron?evi? decided to repeat the same project with older girls, to see how the experience might be different. “It turned out that girls from 17-19 could not have an audience,” she says of her decision to dismantle the car in a private space. By working on the car in seclusion, Ron?evi? says that the girls were able to relax and learn freely. “They felt good because I wasn’t in the position of telling them what to do,” she notes, explaining that because she did not have much practical experience under the hood herself, she encouraged the girls to jump in and do research themselves.

Ron?evi? hopes to expand this project in the future, as well as explore other themes. “I am generally interested in the way art can influence daily life. I have my utopia, an idea that unifies all the issues I have been dealing with for a past few years, so that is what I am heading for.”

Check out more Dina Ron?evi?’s work on her personal website.

Written by Elaine Ritchel (@elaineritchel)